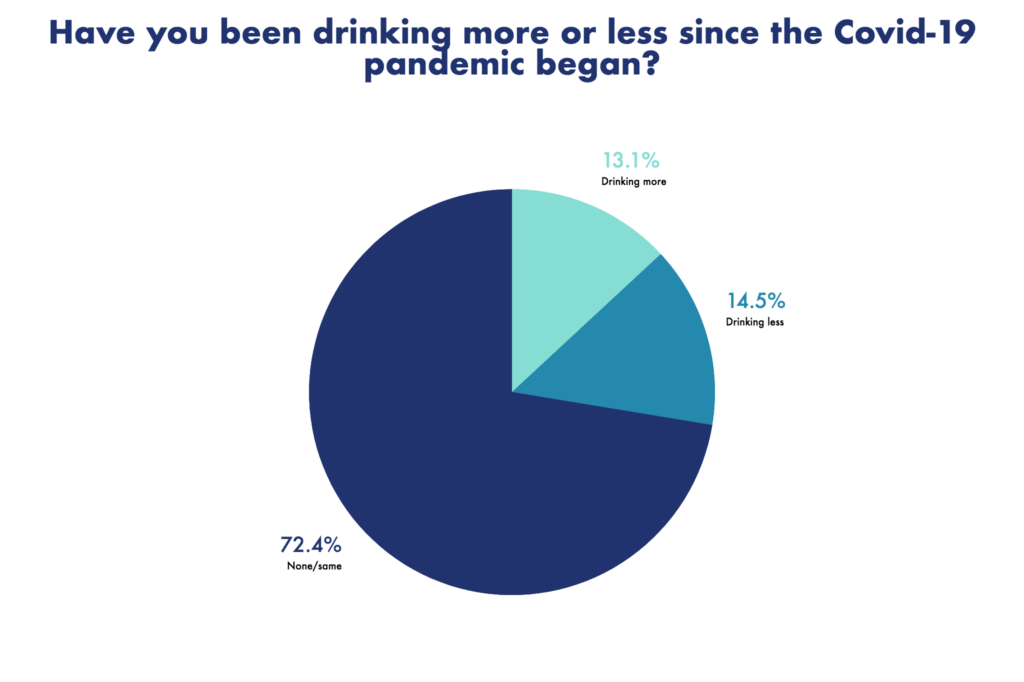

A survey of 500 US adults by Drug Helpline has revealed that most people’s alcohol consumption has not changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found that 13% of Americans have increased their drinking since the virus appeared, while 14.5% have been drinking less.

This shows a nuanced picture emerging: some have made positive lifestyle changes during the pandemic, while others have been drawn into deleterious behavior.

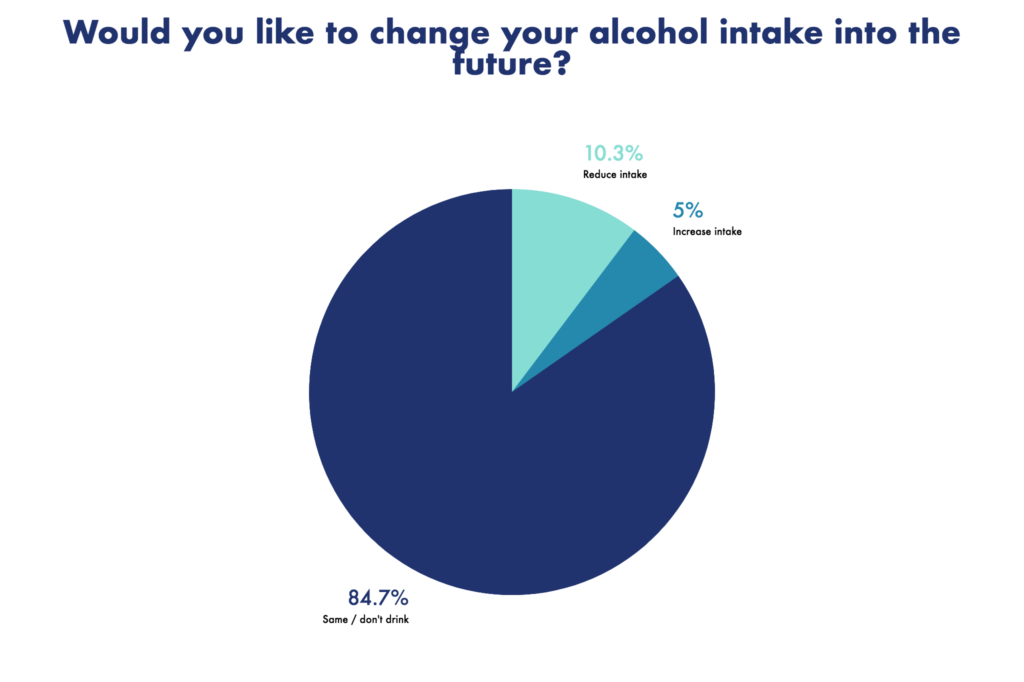

The Drug Helpline survey found that 10% of Americans want to reduce their alcohol intake into the future. It also found that 85% want to keep their drinking the same, which indicates, reassuringly, that the vast majority have kept their alcohol consumption in check during the pandemic.

As the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, it brought a host of secondary effects on determinants of health. On 30th January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the global outbreak of the novel coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern,[1] and on 13th March President Trump announced a “National Emergency.”

Most states then initiated a “stay at home” order for non-essential workers. This began one of the most profound changes in the pandemic: the redistribution of the workforce. Businesses in hospitality and entertainment were closed down, with workers made obsolete almost overnight. In March the federal government passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, a $2 trillion economic relief package designed to help people and businesses affected by the lockdown.

“I anticipate a rise in mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, various substance misuse disorders, and alcohol-related illnesses as a result of increased drinking.”

–– Dr. Samantha Miller, a physician and spokesperson for Drug Helpline

Alcohol Sales

With hundreds of thousands of workers told to “stay at home,” and most bars and restaurants closed, off-premise alcohol sales soared. Weekly sales increased 55% from 2019 as people stocked up on supplies.[2]

Alcohol was considered “essential goods,” so liquor stores were allowed to remain open in most states. As companies adapted to the new circumstances, delivery services became more common and efficient, and home deliveries of alcohol became easier and more acceptable.

Loss of Routine and Alcohol Intake

From March 2020, people were suddenly confined to their homes, often with no work and a limited ability to socialize or engage in recreational events. For some, boredom set in, and alcohol provided a source of entertainment. With less-structured days and no “weekend,” drinking became the norm on any day, at any time.

Since outings in the car were curbed, there was less need to worry about drink driving. People increased their use of social media to communicate and socialize with friends, and with this came virtual happy hours, drinking games, and no queues at the bar. Hashtags like #quarantinis trended.

Drinking at home brings additional considerations. For example, pouring your own drinks can mean consuming larger measures, especially with spirits. At home, especially if you’re drinking alone, there is nobody to tell you when you should stop.

Stress and Alcohol

One concerning reason for an increase in alcohol consumption is as a coping mechanism for the psychological stress of these uncertain times. Stress is a well-established risk factor for the development of substance misuse disorders, including alcohol misuse. With the usual coping mechanisms like socializing and exercising being limited, rates of substance use and addiction are bound to increase.

Many people use alcohol in times of stress, to switch off and relax, and there has been no greater stressor in recent times than a global pandemic. Unfortunately, alcohol is also associated with an increase in stress disorders, such as anxiety and depression, so problem alcohol intake can become a vicious cycle.

Relapse of Alcohol Misuse Disorders

There is also evidence of a higher rate of relapse into alcohol addiction during the pandemic.[3] Social isolation and boredom are recognized risk factors for relapse, and social and mental-health support are essential in any recovery plan, but many in-person support groups have been cancelled.

The long-term public-health implications of relapse into alcohol misuse during the pandemic are unknown as yet. But there is early evidence of an increase in long-term alcohol-related problems such as liver disease.[4]

Finances and Alcohol

The pandemic brought new financial hardship for some, with not everyone eligible for financial relief. Unemployment has soared, and households have less disposable income. Some households have responded by switching to cheaper, lower-quality alcohol: sales of cheap boxed wine is outperforming more expensive bottled wine.

For others, though, alcohol is a luxury, and simply unaffordable in times of financial stress. Even for those with an adequate income, the financial future is uncertain. Many families are trying to save, to protect against future poverty.

Alcohol and Socializing

Many people associate alcohol with social events like drinks after work or a bottle of wine with a meal in town. With bars and restaurants closed, social drinking with family and friends outside the home was no longer possible. For those who only drink alcohol on social occasions, this removed it from their lives entirely.

Even as bars began to reopen, the safety measures of social distancing and mask-wearing made the experience less pleasurable. The overall message was still “stay at home” to avoid transmitting or acquiring the virus, so people were reluctant to go out just for a social engagement. Major events associated with drinking alcohol, such as sports, festivals, and concerts, have also been cancelled, so there are fewer occasions where drinking takes place.

Risks of Alcohol

A WHO publication on alcohol and COVID-19 highlighted the risks of drinking alcohol, such as a weakened immune system and the development of alcohol use disorders. It recommended limiting or removing alcohol from the diet, avoiding consumption around children, and being aware of false claims that alcohol helps protect against viral infection.

There is broad awareness that alcohol is bad for the immune system, and in a global pandemic people are extra aware of keeping their immune system healthy.[5]

Reducing Alcohol Intake

More positively, less time spent working and commuting has given people a unique opportunity for self-improvement, which could include a conscious effort to cut down on alcohol. With fewer social pressures to drink and fewer opportunities to buy alcohol, many people have reduced or removed alcohol from their lifestyle.

Future Alcohol Intake

Alcohol consumption habits have changed dramatically in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a shift from drinking in bars to drinking at home. But it is unclear whether consumption overall has increased or decreased. The public health messages on limiting alcohol remain pertinent, and it remains to be seen if there will be long-term health consequences to increased drinking during the pandemic.

“In my practice, I have encountered patients drinking far more during the pandemic, which is a deeply concerning trend. The latest survey findings show that there has also been a sizeable proportion of the population who have reduced or maintained their drinking levels,” said Dr. Samantha Miller, a physician and spokesperson for Drug Helpline. “In terms of consequences of the pandemic, I anticipate a rise in mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, various substance misuse disorders, and alcohol-related illnesses as a result of increased drinking.”

Published: October 6, 2020

Last updated: February 23, 2023

References

| ↑1 | Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed September 28, 2020. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Alcohol Weekly Sales Growth. Total US All Outlets Combined (xAOC) including Convenience and Liquor Stores. Neilson Retail Measurement Services. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2020/rebalancing-the-covid-19-effect-on-alcohol-sales. Accessed September 28, 2020. |

| ↑3 | Drinking alone: COVID-19, lockdown, and alcohol-related harm. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2020;5:625 |

| ↑4 | Hein, I. Alcohol Abuse Agitated by COVID-19 Stirring Liver Concerns. Medscape. Published May 6, 2020. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/930039. Accessed September 28, 2020. |

| ↑5 | Alcohol and COVID-19: what you need to know. World Health Organization. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/437608/Alcohol-and-COVID-19-what-you-need-to-know.pdf?ua=1. Accessed September 29, 2020. |